How to use AI tools with discernment

Thinking is a human process that cannot be delegated. Always write to build your logic first. Once the hard work is done, use AI to challenge your thoughts, translate ideas, and accelerate execution.

There is a mandate sweeping through every company right now: “Be AI-first.”

I have championed this myself. To me, being AI-first means ruthlessly eliminating friction in individual productivity. But as the months passed, I felt a specific anxiety growing. I realized that AI-first was becoming a trap. It was encouraging us to skip the most painful, inefficient, and essential part of our work: the actual thinking.

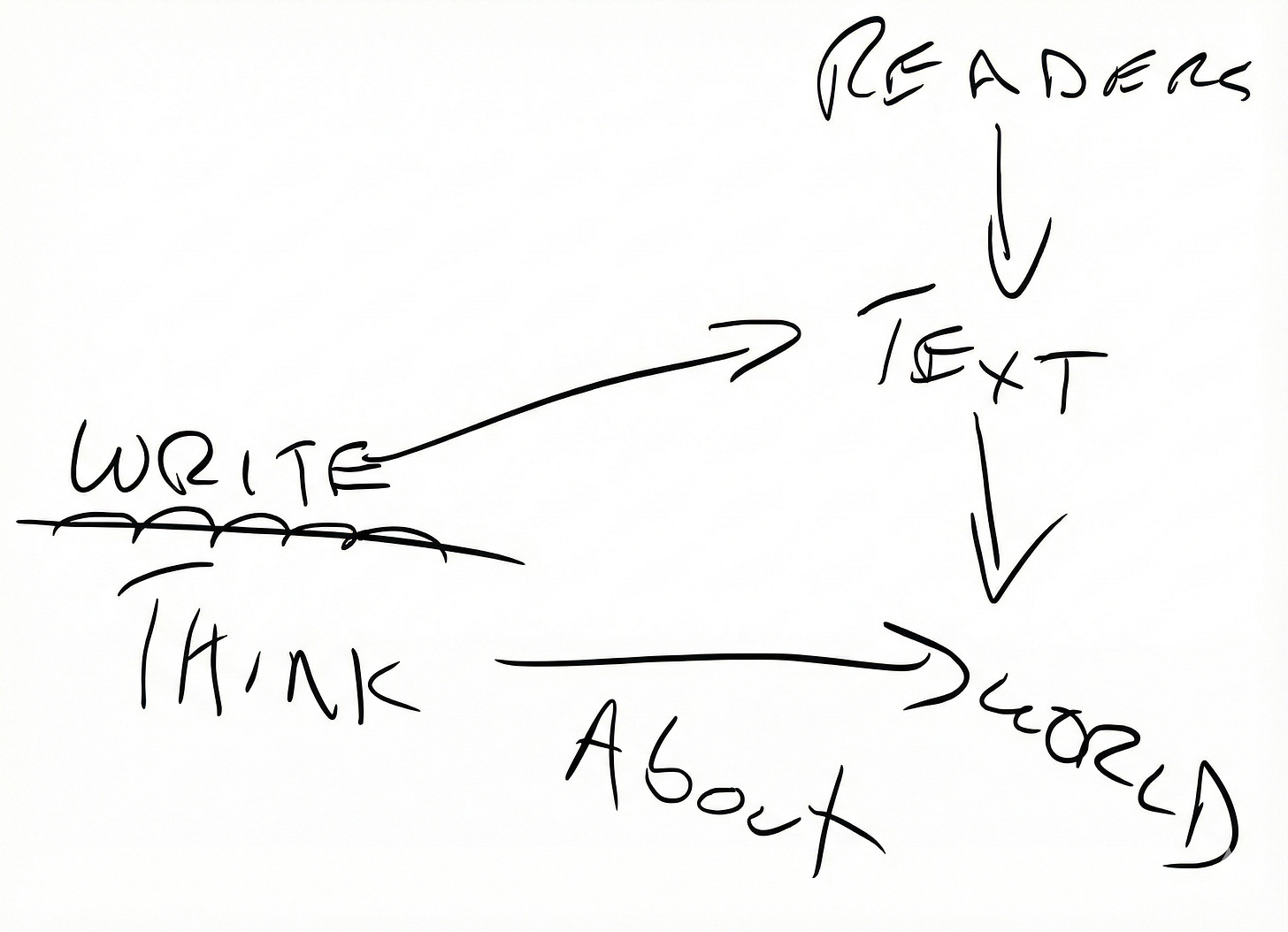

I kept coming back to this diagram (which comes from a resource I will share at the end).

It captures the reality for those of us operating at a sophisticated level, whether you are a product manager, designer, or engineer. We are experts in the problems we solve and the products we build. To navigate that complexity, we must use the writing process to help us think. Only once that deep thinking is done do we switch modes to structure, communicate, and create impact for our readers.

I wanted to formalize a framework for this. But instead of writing a dry manifesto filled with +20 lessons or lists of pros and cons, I decided to tell a short story.

Here it is.

1.

Alex is a product manager. He loves the job for the problem-solving: taking a messy reality and carving out a clean solution. But sometimes, like today, it just feels hard.

He stares at the cursor. It blinks for ten minutes, mocking him. On his second monitor, a spreadsheet with ten thousand rows of user feedback blurs into a wall of grey. He rubs his temples. The data is there, but the insight is buried under weeks of manual tagging.

He sits at his desk in the heart of Paris. Inside, the office buzzes with the sound of deadlines. StreamFlow is a white-label streaming audio company for radios, and right now, the silence of the blinking cursor feels louder than the music.

A notification pings on his screen. It is a company-wide memo from the CEO. The subject line is simple: “The new baseline: our AI-first future.”

He opens the message. It is direct. The CEO writes that the industry is changing fast. He explains that other companies, like Shopify, are already making AI a mandatory skill. He wants StreamFlow to lead, not follow.

“Reflexive AI usage is now a baseline expectation,” the email reads. “We need multipliers. Before asking for more headcount, you must demonstrate why you cannot do the work with AI. If you are not climbing, you are sliding.”

A glance across the aisle confirms the stakes. Ben, the junior PM, is already typing furiously, a faint, satisfied smile on his face. Is Ben climbing? Is Alex already sliding?

Leaning back, he reads the words again. Around him, his colleagues read silently, absorbing the shift.

A surge of electricity hits him. It feels like relief.

For years, product management feels like heavy lifting. It means endless documentation, slow discovery phases, and fighting for resources. Now, the CEO hands him a jetpack. The memo gives him permission to stop walking and start flying. He imagines a workflow without friction.

To Alex, being AI-first means treating AI as his primary thinking partner and operational engine. It means his default instinct for any task, whether strategic analysis, requirement writing, or data querying, is to first ask, “How can Gemini start this for me?” rather than opening a blank document.

2.

Elena, the VP of product, walks over to Alex’s desk. She looks focused and energetic.

She leans against the edge of his desk.

“Project SonicGraph. It’s a mess, Alex.” She sighs. “Fifty million songs and zero metadata. Clients are churning because they can’t distinguish a ballad from a banger. I need a miracle, and I need the rollout plan by Friday.”

Alex nods. The mission is to build an intelligent layer that listens to the raw audio and generates rich, descriptive tags (mood, tempo, energy) at a scale no human team could touch. In the old world, this is a six-week work. It requires user interviews, data sampling, and tedious alignment meetings.

But this is the new world.

Alex looks at the empty document on his screen. He does not feel the crushing weight of fifty million songs. He opens a new tab. He navigates to Gemini. The cursor blinks, waiting for his command. It feels like a magic wand, heavy with potential.

“Time to multiply,” he whispers.

He cracks his knuckles. He is ready to prompt.

3.

“Act as a chief product officer,” he types. He types the invocation carefully, using the words he knew the machine loved: “scalable,” “high-velocity,” “AI-powered.” He wasn’t asking a question; he was entering a cheat code. “Define the product strategy for project SonicGraph. Prioritize high-velocity metadata ingestion using LLMs. Include success metrics, risk assessment, and a technical rollout plan.”

He hits Enter.

The magic is instant. The response doesn’t just appear; it assembles itself. Perfectly indented bullet points, bolded headers like “strategic Imperatives,” and a confident summary at the end. It wore the costume of competence so perfectly that Alex doesn’t notice the mannequin underneath.

Alex feels a rush of intellectual vanity. He looks at the words “high-velocity ingestion” and nods, as if he had thought of them himself. The gap between prompting the idea and having the idea vanished. Usually, drafting a strategy is painful. It requires staring at a blank wall, wrestling with doubts, and forcing his brain to connect dot to dot. It is high-friction work.

But this? This is effortless. It is the digital equivalent of fast thinking, that automatic, intuitive mode where the brain jumps to conclusions without the pain of deep analysis. He feels no cognitive strain. He tells himself this is exactly what the CEO demanded. This is the AI-first mindset. He isn’t cutting corners; he is being a multiplier.

He leans forward. He wants more.

“Generate a detailed PRD based on this strategy,” he commands. “Include user stories and acceptance criteria.”

The document appears. It has tables. It has “must-haves” and “nice-to-haves.” It looks exactly like the work of a Senior PM, but it takes thirty seconds.

“Now, visualize the architecture,” Alex types. “Create a sequence diagram for the metadata ingestion pipeline.”

Alex nods in satisfaction. The diagram is a dense thicket of boxes and arrows. It looks impressively technical, unassailable. It is a shield. Who dares ask about user interviews when faced with a diagram of “asynchronous metadata latency checks”?

He feels invincible. He looks at his screen and sees artifacts that usually take weeks to produce. He has a 10-page PRD. He has a technical diagram. He has a strategy.

He opens a slide deck. He copies and pastes the AI’s output into the slides. He adds confident titles. He adds the sequence diagram to slide five.

He scrolls through the output. It is dense with the kind of complexity that commands respect in meetings. He hasn’t spoken to a single user. He is moving at the speed of making, bypassing the slow, messy friction of the old world. He is doing exactly what the CEO asked: he is multiplying his output without multiplying his headcount.

He looks at the clock. It is 11:00 AM. He has finished the job.

4.

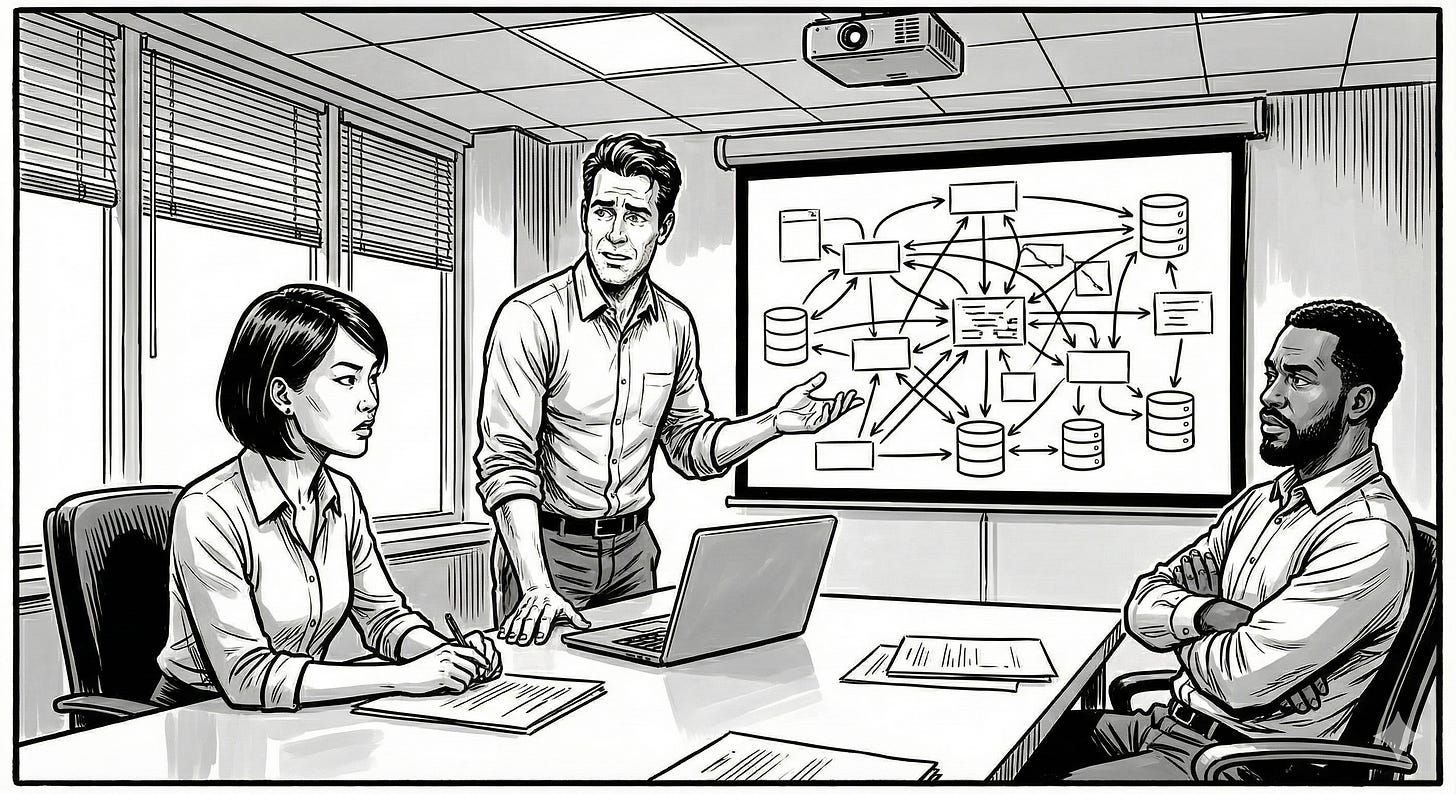

It is Friday morning. Alex walks into the discovery review ritual.

The room is full. Elena, the VP of product, sits at the head of the table. To her left is Marcus, the staff engineer. He is quiet, sharp, and known for suffering no fools. The lead data scientist joins via video link.

Alex connects his laptop. He projects the SonicGraph deck.

He stands up and waves his hands at the screen.

“We are going to leverage high-velocity LLMs,” Alex says. “We will ingest fifty million songs. We will generate rich metadata at scale. We will solve the discovery problem.”

He clicks through the slides. They are beautiful. The sequence diagram filled the screen. It was a masterpiece of complexity: arrows looping back on themselves, database cylinders stacked like pancakes. To Alex, it looked like architecture. To Marcus, it looked like spaghetti code dressed up in a suit.

“As you can see,” Alex says, pointing to the data he did not verify, “our strategy focuses on Lyrical Sentiment analysis to drive user engagement.”

He smiles. He waits for applause. He expects them to be impressed by the speed of the output.

“Alex,” Marcus says. His voice is low, barely cutting through the hum of the projector. “Slide four. You prioritize ‘Lyrical Sentiment’ tags over ‘Instrumental Complexity’.”

Alex doesn’t flinch. He doubles down. He points to the impressive graph on the screen.

“Absolutely,” Alex says, his voice projecting confidence. “It’s about engagement. The industry is pivoting to narrative-based discovery. If we want to reduce churn, we need to give users an emotional hook. Lyrics are that hook.”

He sounds like a visionary. He sounds like the TechCrunch articles the AI was trained on.

Marcus leans back, crossing his arms. “That’s a fascinating theory for a B2C app,” he says. “But eighty percent of our B2B clients are instrumental lo-fi radios for coffee shops. They don’t have lyrics. They have beats.”

Marcus pauses, his eyes locking onto Alex.

“Our churn data shows they leave because they can’t distinguish between ‘Upbeat’ and ‘Melancholic’ tempos. They are begging for key analysis, and you are giving them poetry.”

Alex didn’t back down. He believed the AI’s logic. “That’s the old model, Marcus,” he countered, echoing the report he’d just generated. “The market is saturated. The data shows we need a strategic pivot to capture high-intent users through narrative. We aren’t serving background noise anymore; we are selling a story.”

Elena raised a hand, cutting him off mid-sentence.

“Alex, hold on,” she said. Her voice wasn’t angry, but it was final.

Alex closed his mouth. The silence in the room felt heavy.

She leaned forward. “Forget the LLMs for a second. Picture Hans. He runs a café in Berlin. It’s 7:00 AM, he’s out of oat milk, and the wifi is spotty. He needs a vibe, not a poem. Explain to me, without using the word ‘sentiment,’ how your lyrical tag helps him pour coffee faster.”

The room goes dead silent.

Alex stares at the slide. He desperately scans the bullet points the AI wrote. He looks for the user journey. He looks for the workflow. His fingers twitch under the table. He has a frantic urge to open a new Gemini tab and type: “Explain how a Berlin barista uses lyrical tags for coffee workflow.”

He looked down at his beautiful, AI-generated script: “synergistic tonal shifts,” “narrative-driven discovery,” “high-velocity ingestion.” They were just sounds. In the face of a real user problem, they evaporated.

The VP closes her laptop. The sharp click echoed in the quiet room.

“This is plausible,” she says, her voice cold. “But it is not true. You have generated a lot of text, but you have not made a single decision.”

She stood up. She looked at the blank screen, then back at Alex.

“You have until Monday,” she said. “Come back with a strategy, not a simulation. And Alex? Leave the generator alone. Bring me your brain.”

The meeting ends.

Alex stands alone in the room. He feels cold. He remembers Warren Buffett’s famous warning: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

5.

Alex returns to his desk. He sits in silence. The shame burns hot in his chest. The urge to fix the mistake quickly is overwhelming. It is a physical itch. He reaches for his laptop. His fingers hover over the keys. He opens a new tab. He starts to type: “How to justify metadata strategy to skeptical...”

He stops. The cursor wasn’t just blinking; it was pulsating. It whispered, “I can fix this. Just ask me. I’ll make you smart again.” It offered the ultimate narcotic: the removal of uncertainty. Closing the laptop felt like slamming a door on a friend.

He slams the laptop shut. The screen goes black.

He breathes heavily. He feels the withdrawal. His brain is screaming for the dopamine hit of instant answers. It wants the autocomplete. It wants the machine to fill the silence.

He opens a drawer and digs out a black paper notebook. He finds a pen.

Paper has no backspace. When he wrote a bad sentence, it stayed there, staring at him in permanent ink. The friction of the pen against the page forced him to slow down. He couldn’t move faster than he could think. It was excruciating.

He decides to do the hard thing. He writes the title: “The SonicGraph strategy.”

He stares at the page. The paper stays white. The silence of the room begins to crush him. It is loud and accusing.

He writes a sentence: “We need to tag all songs to improve discovery.”

He looks at the ink. It is generic. It is weak. It is a “jumble of half-baked impulses.”

He rips the page out. The sound tears through the quiet office. He crumples it into a ball and throws it.

He tries again. He writes another sentence. “The goal is high velocity.”

No. That is the lie. He crosses it out so hard the pen tears the paper.

He felt a physical tightness behind his eyes. It was the burn of working memory trying to hold three conflicting constraints, B2B clients, messy data, and zero budget, at the same time. He wanted to check Slack. He wanted to check the weather. Anything to drop the weight. But he held it.

He forces himself to think about Marcus’s question.

“Why do users actually leave?”

He writes the answer: “They leave when the radio plays a techno track in a jazz playlist.”

He stops. He taps the pen on the desk.

“The problem is not that we lack tags. The problem is that the existing tags are wrong.”

The AI strategy was “high velocity generation.” That was the trap. Speed amplifies mistakes. If the current tags are bad, generating 50 million more bad tags at light speed is not a solution. It is a disaster.

The strategy must change. It shouldn’t be “generation.” It must be “correction.”

He feels a click in his mind. This is the insight. The AI did not see it because the AI predicts the average of the internet. It does not know the specific pain of StreamFlow’s users.

But he needed to be sure. He couldn’t just prompt his way to the truth; he had to unearth it.

He opened Slack. He called the account manager for “Bean & Brew.” He asked about their morning routine. He learned that the barista hates the “Skip” button because his hands are wet.

He opened the raw server logs. He didn’t ask the AI for a summary; he scrolled through thousands of rows of ‘Skipped_Track_Events’ until his eyes watered. He saw the pattern: users didn’t skip bad songs; they skipped jarring transitions.

He walked over to the sales corner. He asked Sarah, the lead sales representative, why the last three deals fell through. “They don’t trust our tagging,” she said. “They think we guess.”

This was the raw material. This was the messy reality that didn’t exist in Gemini training data.

He returned to the notebook. He drew a box labeled “the tag filter.” Instead of the system creating tags, the system will sit between the database and the user, flagging errors. It wasn’t a creator; it was a bouncer.

He writes faster now. The ink flows. He maps out the logic.

Insight: Users measure value by outcomes, not by how smart the model is.

Strategy: Trust is the product. We must prioritize precision over coverage.

Tactic: We will use the tech to flag conflicts, not to blindly overwrite them.

He writes for two hours. He sweats. This is the cognitive gym. He is breaking down the muscle fibers of his brain to build them back stronger.

He looks at the notebook. It is messy. It has arrows and crossed-out lines. It is ugly.

But it is grounded. It comes from the hard work of thinking, not the probability of a model. The pages are filled with iterations of diagrams, sketched and re-sketched until he found the best way to represent the situation.

The feeling wasn’t the sugary rush of generating a thousand words in a second. It was the savory, slow-burn satisfaction of finding the one right word. He felt solid. He wasn’t relying on a hollow shell anymore; he had built a structural beam.

He is no longer hollow. He is solid.

6.

Alex thinks back to the CEO’s memo. It warned that “a lot of people give up after writing a prompt and not getting the ideal thing back immediately.” “Using AI well is a skill that needs to be learned,” the email had said. Alex realizes his mistake wasn’t using the AI tool; it was surrendering to it. He decides to try again. But this time, the dynamic is different.

Alex opens his laptop. The screen glows in the dim light of the office.

He opens Gemini. The cursor blinks. It looks the same as before, but the dynamic has changed. Yesterday, Alex surrendered the wheel. Today, he is in the driver’s seat, with the AI as his navigator.

He types. He does not ask the AI to think for him. He feeds it the logic from his notebook to check his blind spots.

“Context: You are a data analyst. Constraint: Do not generate new ideas yet. Input: The logic from my notebook below. Task: Identify assumptions in this logic regarding data latency that I might have missed.”

He hits Enter. He waits.

Now, he uses the AI as a sparring partner.

“Act as a skeptical staff engineer,” he prompts. “Find three flaws in this logic. Tear it apart.”

The AI argues that flagging conflicts might increase user friction. Alex shakes his head. “Incorrect,” he types back. “Backend flagging is invisible to the user. Re-evaluate based on backend-only implementation.” The AI apologized and corrected its model. Alex smiled. He is co-constructing the solution. He does not blindly accept the critique; he engages with it. He refines his argument. He fixes the holes. He is using the tool to sharpen his blade, not to fight the battle for him.

Then, he uses the AI as a translator.

“Convert this narrative into a technical PRD,” he prompts. “Maintain the logic exactly as written, but format it for the engineering team.”

The document appears. It is perfect. The formatting is fast and cheap. The logic is slow and valuable. The combination is powerful.

But Alex needs one more thing. He needs to win back Marcus, the staff engineer. He needs proof, not just words.

Alex is not a coder. In the old world, he would have to wait days for a data analyst to pull the numbers. But the boundaries of his role have blurred. Range has become an edge.

He types a new command. It is a spell he could never cast before.

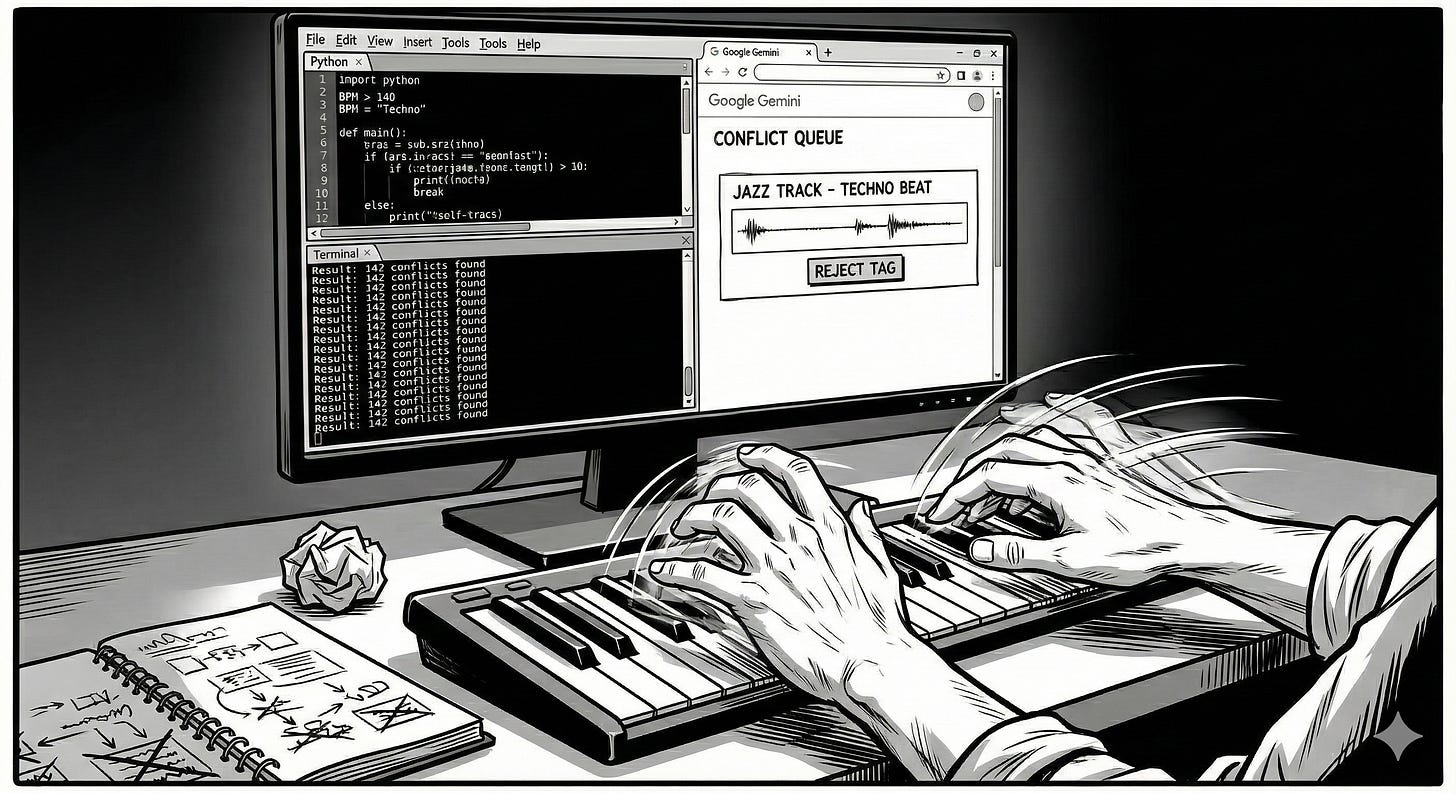

“Write a Python script to query the StreamFlow API. Scan the top 1,000 songs tagged ‘jazz’. Identify how many have a BPM higher than 140 and contain the tag ‘Techno’.”

The AI writes the code. Alex copies it.

Alex runs the code. Red text flashes. 0 conflicts found.

Alex frowns. That isn’t right. He knows the data is messy. He looks closely at the new code. He spots the lazy fix: inside the error handler, the AI added a break command. It stopped the entire script at the first sign of trouble.

He types back, correcting the logic, not just the syntax: “You used break, which stops the scan. Use continue to skip only the bad record.”

The AI apologizes and rewrites the loop. Alex nods. He isn’t just commanding; he is supervising. He copies the new code and runs it again.

The screen wasn’t pretty. No gradients, no drop shadows. Just a black terminal window with white text scrolling fast. It was the ugliest thing he had produced all week, and it was the only thing that was true.

Result: 142 conflicts found.

Alex smiles. He has the data. But Elena needs to see the concept, not just the problem.

He types one last command: “Build a simple HTML/JS interface for the ‘conflict queue’. Show the ‘jazz’ track with the ‘techno’ beat. Add a ‘reject tag’ button. When clicked, it shouldn’t just delete the tag; it must log the rejection as a negative training example to update the classification heuristic.”

He runs the code. A window pops up. It is a working prototype. He clicks the button. The bad tag vanishes. It isn’t a slide deck promise anymore; it is a tangible product.

He feels the sheer weight of 50 million rows of data. It was too heavy for a human brain to lift, but with the Python script and the prototype as his hydraulic lift, he moves it with a flick of his finger. He isn’t pretending to be strong anymore. He is piloting a machine that made him strong.

He prints the report. He picks up his notebook. He is ready for the review.

7.

The following Monday, the team gathers for the SonicGraph alignment meeting.

Elena sits at the head of the table, waiting. To her left, Marcus sits with his arms crossed. They expect another slide deck. They expect more bluster.

Alex walks in. He connects his laptop.

He doesn’t project a slide deck. The screen shows a raw, ugly web interface. It has no logo, no branding, just a list of songs and a button that says REJECT TAG.

“I built a prototype,” Alex says.

He clicks the first item: a smooth jazz track labeled “techno.” He hits the button. The bad tag vanishes instantly.

“When I click reject,” Alex explains, “it doesn’t just fix this one song. It feeds a negative example back to the model. We aren’t trying to manually tag 50 million songs. We are building a feedback loop to fix the filter that tags them.”

Marcus leans forward. He stops spinning his pen. “You built this?”

“I built the interface to verify the logic,” Alex says. “Because we can’t just generate tags. We have to verify them. This tool is the strategy.”

He hands out the six-page narrative document. “This explains the ‘why.’ The prototype shows the ‘how.’ But the core is simple: Trust is the product.”

Marcus reads the document. He sees the change immediately. The generic buzzwords are gone. Instead, he finds a logical argument about trust vs. coverage.

Alex pointed to the graph on page four. “We are currently optimizing for coverage (tagging everything). This destroys trust. We need to optimize for precision (tagging only what we know is true).”

“Page three,” Marcus says, looking up. “You argue that we should flag conflicts rather than overwrite them. You claim 15% of our ‘jazz’ tracks are mislabeled.”

“About fifteen percent?” Marcus asked.

“Fourteen point two percent,” Alex corrected. He didn’t offer a rounded-up guess. He offered a calculated fact. “I ran the script against the full dataset this morning.”

Marcus looked at Alex, then at the code snippet stapled to the back. The look of suspicion vanished, replaced by the look an engineer gives a partner who finally understands the problem.

“This is real,” Marcus says. “We can build this.”

The tension in the room vanishes. The team is not just moving fast; they are moving together. The alignment is solid because the thinking was solid.

8.

That evening, Alex sits at his desk. He looks at the AI-first memo from the CEO that started it all. He realizes that even the leadership might be lost in the hype, confusing motion with progress. True AI-first requires discernment, not just a blind reflex. You have to use the tool constantly at first to build intuition, but only so you can learn exactly when to ignore it and think for yourself.

He opens a new document. He writes a note to himself, a spell-book for the modern age.

Rule 1: Write to think. Never prompt until you think, and to think you have to write. Text is the interface of the mind. If you cannot write the argument yourself, you do not understand the problem. The AI can polish your logic, but it cannot invent it.

Rule 2: Delegate execution, not responsibility. Treat AI as a colleague. Delegate tasks for speed and quality, but never the full workflow. Just like managing a team, you can transfer the execution, but you can never transfer the responsibility. Supervision is essential.

Rule 3: Extend capabilities, don’t replace effort. Use AI to extend your capabilities, not as a replacement for your hard work. Write the code. Analyze the data. Use it to widen your range, not to narrow your responsibility.

Alex closes his laptop.

He is still an AI-first product manager. He uses Gemini every day. He moves faster than ever. He understands the real work now. He refuses to delegate the thinking; instead, he uses the time saved to go deeper and slower. Once the core thinking is solid, he shifts gears, using Gemini to move at light speed: translating ideas for different audiences, building prototypes, and rigorously challenging his own assumptions.

The core lesson of Alex’s journey is simple: write to think, then prompt AI to execute.

Here are three resources to use AI tools with discernment:

Larry McEnerney, The Craft of Writing Effectively. This training session is the source of the diagram in the introduction. Larry McEnerney explains that experts use writing to think through complexity. But raw thinking confuses readers. You must write to solidify your logic first. According to me, this is where the AI framework fits: never use AI for thinking. Write to build your logic, then use AI to translate it.

Paul Graham, Writes and Write-Nots. Graham argues that writing is hard because it is thinking. Because AI can now do the writing, fewer people will learn the skill. Graham warns of a future divided into “writes and write-nots.” If you give up writing, you give up thinking. Writing is now a deliberate choice to remain capable.

Hiten Shah, What AI Really Did to Product Teams. AI increases the speed of making, but not the clarity of thinking. Shah explains that prototypes now arrive before the problem is clear. This shifts the burden to human judgment. As Shah notes, “ideas are abundant,” but “judgment is scarce”. To win, you must prioritize clarity over speed.

I’m curious to know how you are navigating this shift. When was the last time you forced yourself to write before opening an AI tool? Did the friction feel like a waste of time, or did it change your final output?